Bodywork progress

Work is progressing on the bodywork.

GROUND EFFECTS

For 50 years racing cars have utilised wings (inverted airfoils) to increase the levels of grip provided by the tyres. 35 years ago another aerodynamic device called 'ground effects' was introduced.

The 'ground effect' phenomenon is based on Bernoulli’s equation, known as one of the basics of Fluid Mechanics Theory, that states the following: if fluid flows through a constriction, its speed will rise and pressure will fall. Applied on a racing car, this theory goes like this: air is a fluid. If the bottom of the car is shaped correctly, it is possible to create a low-pressure area under the car. Car will literally be sucked to the ground. That phenomenon is known as ‘ground-effect’. Since the cornering speed depends on friction between tyres and tarmac, and friction depends on vertical force which is equal to the sum of car’s weight and negative lift force generated by low pressure area beneath the car; the bigger the pressure-fall is, the better the car performs.

The Bernoulli principle is not the only scientific component in generating ground effect downforce. A large part of ground effect performance comes from taking advantage of viscosity. The boundary layer between the two surfaces works to slow down the air between them which lessens the Bernoulli effect. However when a car moves over the ground the boundary layer on the ground becomes helpful. In the reference frame of the car, the ground is moving backwards at some speed. As the ground moves, it pulls on the air above it and causes it to move faster. This enhances the Bernoulli effect and increases downforce. The beauty of 'ground effects' is that, unlike wings, it produces downforce with minimal drag.

Part of the danger of relying on ground effects to corner at high speeds is the possibility of the sudden removal of this force; if the belly of the car contacts the ground due to a bumpy track surface, the flow is constricted too much, resulting in almost total loss of any ground effects. If this occurs in a corner where the driver is relying on this force to stay on the track, its sudden removal can cause the car to abruptly lose most of its traction and slide off the track. This effect was part of the reason why the FIA banned ground effects in some categories in 1982. Today's tracks are much smoother and this issue is not the problem it used to be.

Ground effects were banned in Europe at the end of 1982 in some categories on issues of safety, and at the end of 1986, Australia followed. The new regulations saw flat-bottomed cars with only a rear diffuser shaped for creating downforce. Formula One cars now generate a proportion of their overall downforce by the following effect: the chassis is raked - ride height is low at the front and higher at the rear, vortices generated at the front of the car are used to seal the gap between the sidepods and the track and a small diffuser is permitted behind the rear wheel centerline to slow down the high speed underbody airflow to free-flow conditions. This is a crude solution compared to an inverted wing, but incredibly complex development and research, only available to multi million dollar race teams, have enabled today’s F1 to produce substantial ground effect downforce - and the ground-effect story continues. For the rest of the racing world, not constrained by FIA rules, the inverted wing inside the sidepods is still the most effective solution.

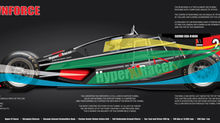

The Hyper X1 Racer is a proper 'ground effects' racing car. The Hyper Racer company is uniquely equipped to design, build and develop a 'ground effects' racing car. Co-designer, Jon Crooke, won the 1986 F2 Australian Championship driving a ground effects racing car. His driving experience of 'ground effects' cars, plus Dean Crooke and Jon's understanding of aerodynamics is invaluable in developing the X1 aerodynamics package. Dean's experience with Nissan Motorsport in composite carbon / kevlar construction completes the aerodynamics team.

Jon Crooke - 1986 Formula 2 Australian Champion - 7 wins from 9 starts. 5 lap records. 7 fastest laps. 7 poles.

Jon starts the build of timber bucks (patterns). The first job is the ground-effects undertray.

The air intake duct (blanked off in the picture above) is designed to scoop in as much clean air as possible coming from the underside of the front wing assembly. The tunnel then narrows down to speed up the air flow. The narrow point in the tunnel is called the throat, and is where the downforce is made. The position of this throat is critical to the balance of the car. The air then travels to the rear of the tunnel where it expands creating a low pressure area which in turn promotes even faster air velocities in the throat as the air from the throat rushes into the low pressure area at the exit of the tunnel. On the track the tunnels provide the bulk of the downforce, with the front and rear wings being adjusted to provide the final balance of the cars handling.

The air tunnels are designed to sneak in under the rear drive shafts and rear upper suspension wishbones, while at the same time expanding to the largest possible opening at the rear. The interior of the tunnels must be smooth with no sudden changes of direction or protrusions to disturb the air flow.

On top of the ground effects tunnels, Jon builds the sidepods (radiator ducts). All these structures are built to millimeter accuracy. Jon builds the left side of the car first and then builds an exact 'mirror' structure on the right side of the car.

The structure is then filled with expandable foam to provide strength and maintain the curves in the panels for the remainder of the process of mold building. Dean steps in and performs his magic with bog and sand paper, to build in and refine the details.